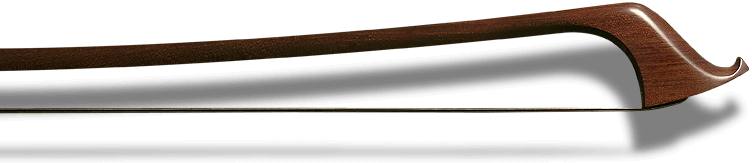

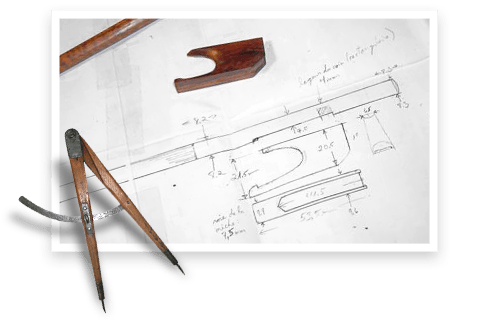

Our knowledge of period bows is based, in part, on the study of original ones preserved in historical collections.

But, as extant bows prior to the 18th century are very rare, the bow maker must turn to other sources. The information on these early bows is mainly to be found in the iconography.

Fortunately, 16th and 17th century paintings are very realistic and the information that they provide with can be supported by several writings: historical teaching methods, treatises on instruments and compositions which give an idea of the sound aesthetic of the period.

As for the medieval era, we cannot rely on written souces : there are very few treatrises on instruments and even no music strictly composed for any bowed instrument. Visual representations, however, are numerous, but they are difficult to exploit. Sculpture, which is a rich source of information for instrument makers, is not very helpful to bow makers. Very few bows were carved in stone because they were long and thin and were too fragile. They are often broken or simply absent.

Thus we must resort almost exclusively to miniatures from manuscripts, even though their analysis requires caution. These miniatures are quite stylized. They suggest more than they describe. However, it is necessary to immerse oneself in them and not to neglect the pictures which seem whimsical at first glance .

A shallow approach of the iconographical material often leads to reject the most puzzling representations and to consider them as the artist's fancies. But a thorough examination of a large number of illustrations gradually reveals recurrences of shapes and details. And very often a classification emerges from these repetitions. If this typology can be linked to an organological or musical evolution, it fully justifies the relevancy of iconographical evidence.